Dance Baby

John Ward Knox at A Centre for Art

Essay by Sam Rountree Williams

John calls what he does a dance. His movements are slow and ordered, perhaps even cautious: this is a funny kind of dance, particularly in light of the show's title, Dance Baby. For me, such a title neither evokes John's dance, nor ballet, ballroom. Instead, what it suggests is something more creative and intuitive, something rhythmic and intensive (possibly even something smutty. I hope not).

John dances outside the Aotea Centre, which is the hub of Auckland's performing arts community. A lot of dancing goes on in there, too, but I don't imagine a lot of it would evoke comments such as “dance baby”. What goes on in there is a form of dancing that reinforces the apparatus of the State, and has a privileged status as official Culture.

As I understand it, dance which comes under the official `Arts' umbrella consists of two primary components; intertwined and inseparable though these may be. The first component involves the order; the time structured by intervals; the choreography which describes the precise arrangement of limbs and dancers at any given point, as in a Muybridge series. The second component sees the first as illusory: it understands time as duration, and the dance as indivisible rhythmic movement and intensity. It cannot see the trees for the woods, so to speak. The second is precisely that which cannot be systematised in the dance; is in excess of the dance's structure; and is always where the truly creative and subversive elements of dance reside.

Dance at a rave, at a concert, or impromptu in the street all seem to revolve around this intensive component of State dance, excluding the order entirely. There is no planning, are no steps; there's just rhythm, movement and feeling. While State dance is an outlet for the subversive currents in society though (more significantly) a reclaiming of territory - bringing such movements back under State control - the other kind of dance (the one that just makes you wanna dance, baby) can be a bit uncomfortable for the State apparatus. It is unpredictable, contagious (it runs individuals into multiplicities), unreasonable and is often associated with more dangerous subversions such as illegal drugs (!).

With all this talk (mine, not John's) of the State and subversive forces, one might almost be fooled into thinking that John's dance is some sort of activism, or a `political statement' (though I can't imagine what he would be saying). The particular public space he has used in conjunction with the title might suggest as much as well - even if the statement was not an entirely serious one. If this were the case however, John has gone about it in exactly the wrong way - what he has done has been to reverse those interlocking terms of State dance.

Instead of taking the established Newtonian model of time as ordered intervals as his starting point, John has begun with Deleuze and Guattari's subversive notion of the diagram: he has not set out to trace a pre-conceived plan onto a chosen space, but instead the dance is a creative mapping of a drawing made in relation to a ready-made arena. Ironically, what should be a rhythmic and intuitive process is overcoded; pulled back towards State control in its slow and structuring steps. Watching him is often the inverse experience from watching State dance: it is the order that impresses itself upon our sensibility, rather than the creation.

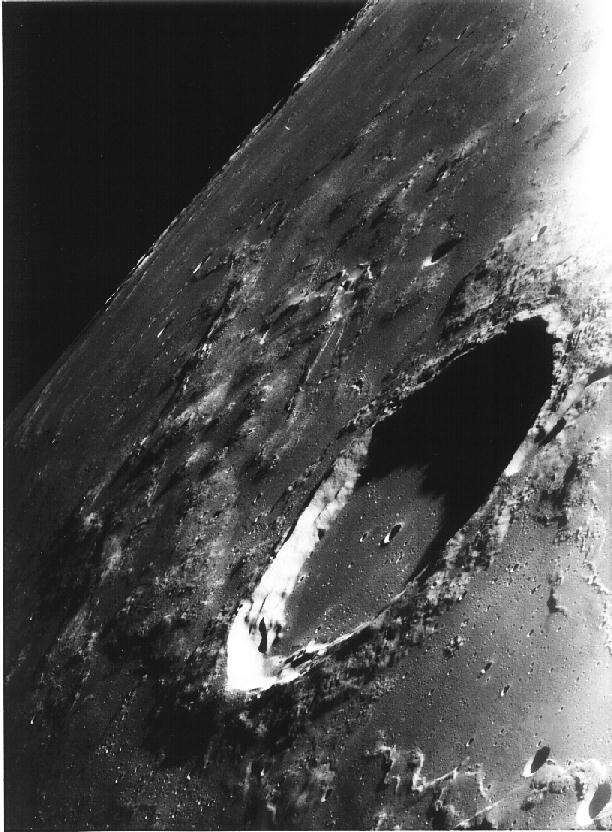

If this were some form of activism it surely would have to aspire to the conditions of Dance Baby dance, rather than make such a humorous hash of State dance's subversion. Remembering that John's dance, like that which takes place inside the Aotea Centre, does live in the shadow of the 'Arts' and 'Culture' umbrellas (though his subheading might be 'Fine Arts' rather than 'Performing', his gesture (on one level) reveals a kind of hopelessness in the subversive endeavours of the Arts. He has the right intentions, seemingly the right approach, but some invisible force reins him in and sucks out the rhythm, the intensity, the movement. Though he tries to map a flower, the organic integrity of this image is lost as the nature of his architectural environment (based on a spatial grid) bears down upon him.

But hey, let's not get hung up about it: this isn't a sad thing in John's work. Why call the show Dance Baby? Maybe it is enough to know that to explain would be to kill the joke - what it does is throw the whole project into a peculiar light and opens it to new registers of meaning. And it is here that the beauty of the thing lies: in holding together related (or not so related), though partially contradictory, elements. As much as there is a register of meaning involving try-hard activism, there is a footnoted wink from the artist, and then several other registers to grapple with also. John's alchemy uses non-resolving elements in a way that generates quirky tensions. He wants to have his cake and eat it too: affirming the artist as shaman - someone who can reveal the absurdity of reason and the oppression of the State apparatus, and discover something lost on the Western individual - while simultaneously parodying that romantic notion.

In particular, John's gesture uses dance (among other things) to make transparent the funny tension in which we are held as contemporary practitioners, between a cynicism born of a distaste for early Modern ideas of primitivizing in art (he wears a generalised `tribal' outfit); for late Modern ideas of creative, expressive, transcendent subjectivities; for the politicised projects of many (70s) artists in their distaste for the first two; and at the same time, a will to embrace all the above for its unflinching enthusiasm and, in some cases, its mysticism. Above all, though, it is the funny, beautiful moments which result from holding all of the above together that create the magic one is drawn to.

Gilles Deleuze and Felix Guattari, A Thousand Plateaus: Capitalism and Schizophrenia, trans. Brian Massumi, Athlone Press, London, 1988.

Monday, November 26, 2007

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

No comments:

Post a Comment